African nationalism

Tuesday, September 10, 2024

Thursday, August 15, 2024

Why Hillter hated the Jewish people.

Adolf Hitler’s animosity towards Jewish people was rooted in a complex interplay of historical, social, and ideological factors that culminated in the catastrophic events of the Holocaust. Understanding Hitler’s hatred requires an examination of various elements, including his personal beliefs, the socio-political context of early 20th-century Europe, and the broader anti-Semitic traditions that existed long before his rise to power.

Historical Anti-Semitism: Anti-Semitism has deep historical roots in Europe, often fueled by religious differences, economic competition, and scapegoating during times of crisis. Jews were frequently blamed for societal problems, including economic downturns and social unrest. This long-standing prejudice provided fertile ground for Hitler’s ideology.

Personal Ideology: Hitler’s own views on race were heavily influenced by pseudo-scientific theories that categorized humans into hierarchies based on racial purity. He believed in the superiority of the “Aryan” race and viewed Jews as racially inferior and a threat to societal cohesion. His writings in “Mein Kampf” articulate these beliefs, portraying Jews as a dangerous enemy who undermined German society.

Socio-Political Context: The aftermath of World War I left Germany in a state of turmoil, with significant economic hardship and national humiliation due to the Treaty of Versailles. In this context, Hitler exploited existing anti-Jewish sentiments to unify his followers against a common enemy. He portrayed Jews as responsible for Germany’s misfortunes and used propaganda to dehumanize them.

Nazi Propaganda: The Nazi regime employed extensive propaganda to promote anti-Semitic views and justify discriminatory policies against Jews. This included portraying Jews as subhuman and as conspirators against the German nation. The regime’s control over media allowed it to disseminate these ideas widely, reinforcing public support for increasingly violent measures against Jewish communities.

Scapegoating During Crises: Throughout history, minority groups have often been scapegoated during times of crisis; this was particularly evident during the Great Depression when economic instability led many Germans to seek someone to blame for their suffering. Hitler capitalized on this sentiment by framing Jews as responsible for both economic woes and perceived cultural decay.

In summary, Hitler’s hatred towards Jewish people was not merely a personal vendetta but rather a manifestation of deeply ingrained societal prejudices combined with his own ideological convictions and the political climate of his time.

How the Orange River become known as orange river

The Orange River, one of the longest rivers in South Africa, has a rich history that contributes to its name. The river’s origins can be traced back to the indigenous peoples of the region, who referred to it by various names in their native languages. However, the name “Orange” is derived from the Dutch House of Orange-Nassau, which played a significant role in the history of South Africa during the colonial period.

In the late 17th century, European explorers and settlers began to arrive in southern Africa. The river was first documented by European explorers in 1779 when Robert Jacob Gordon, a Dutch explorer and military officer, traveled through the region. He named it “Groot River,” which translates to “Great River.” However, it was later renamed after Prince William of Orange, who was a prominent figure in Dutch history and politics.

The name “Orange” became more widely used during the early 19th century as British colonial interests expanded into southern Africa. The British took control of the Cape Colony from the Dutch and established a new colony known as the Orange Free State in 1854. This area was named after the river and further solidified its association with the House of Orange-Nassau.

The river itself flows for approximately 2,200 kilometers (1,367 miles) from its source in the Drakensberg Mountains to its mouth at the Atlantic Ocean near Alexander Bay. It traverses several provinces in South Africa and serves as an important water source for agriculture and industry.

Throughout its history, the Orange River has been significant not only for its geographical importance but also for its cultural implications. It has served as a natural boundary between various groups and has been central to many historical events in southern Africa.

In summary, the Orange River received its name due to European colonial influences and connections to Dutch royalty. Its historical significance is intertwined with both indigenous cultures and colonial expansion.

Cuban missiles

The Cuban Missile Crisis: A Story of Tension and Resolution

In October 1962, the world stood on the brink of nuclear war as the Cuban Missile Crisis unfolded, a pivotal moment in Cold War history that tested the resolve of nations and the limits of diplomacy. The crisis began when American reconnaissance flights over Cuba revealed the presence of Soviet nuclear missiles on the island, just 90 miles from Florida. This discovery ignited fears within the United States government, led by President John F. Kennedy, who faced an unprecedented challenge: how to respond to this direct threat to national security.

The backdrop of this crisis was steeped in historical tensions between the United States and Cuba, particularly following Fidel Castro’s rise to power in 1959. Castro’s alignment with the Soviet Union alarmed U.S. officials, who were already wary of communist expansion in Latin America. In response to previous U.S.-backed attempts to overthrow him, Castro sought military support from Moscow, leading to the installation of nuclear missiles capable of striking major U.S. cities.

As news broke about the missiles, President Kennedy convened a group of advisors known as ExComm (Executive Committee of the National Security Council) to deliberate on possible courses of action. The options ranged from airstrikes against missile sites to a full-scale invasion of Cuba. However, Kennedy opted for a naval blockade—termed a “quarantine”—to prevent further shipments of military equipment to Cuba while allowing time for diplomatic negotiations.

Tensions escalated dramatically as Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev responded defiantly to the blockade. The world watched with bated breath as both superpowers exchanged heated rhetoric and military posturing. On October 22, Kennedy addressed the nation, revealing the existence of the missiles and outlining his administration’s response. He emphasized that any missile launched from Cuba would be met with retaliation against the Soviet Union itself.

As days passed without resolution, fears grew that miscalculations could lead to catastrophic consequences. Back-channel communications between Washington and Moscow became crucial during this period; both leaders understood that they needed to find a way out without losing face or appearing weak.

Finally, after intense negotiations and back-and-forth exchanges through letters and intermediaries, an agreement was reached on October 28. Khrushchev announced that he would dismantle the missile sites in exchange for a U.S. pledge not to invade Cuba and a secret agreement regarding U.S. missiles stationed in Turkey aimed at the Soviet Union.

The resolution of this crisis marked a significant turning point in Cold War relations; it highlighted both nations’ willingness to engage in dialogue rather than resorting solely to military action. Furthermore, it led to increased communication channels between Washington and Moscow aimed at preventing future crises—a legacy that would shape international relations for decades.

Hilter rise to power

Hitler’s Rise to Power

1. Post-World War I Context

Adolf Hitler’s ascent to power cannot be understood without considering the tumultuous aftermath of World War I. The Treaty of Versailles, signed in June 1919, imposed severe penalties on Germany, including significant territorial losses, military restrictions, and crippling reparations amounting to $33 billion. This treaty fostered widespread resentment among Germans, who felt humiliated and betrayed by their leaders. The economic instability that followed—marked by hyperinflation in the early 1920s—further eroded faith in the Weimar Republic, leading many to seek radical alternatives.

2. Early Political Involvement

In September 1919, Hitler joined the German Workers’ Party (DAP), which would later become the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP or Nazi Party). His exceptional oratory skills quickly propelled him into a leadership role within the party. By 1923, he attempted a coup known as the Beer Hall Putsch in Munich, aiming to overthrow the Weimar government. Although this failed and resulted in his imprisonment, it significantly raised his profile across Germany.

3. Mein Kampf and Ideological Foundation

While incarcerated, Hitler wrote Mein Kampf, outlining his vision for Germany and articulating his beliefs about race, nationalism, and anti-Semitism. He argued for a strong authoritarian state led by a singular leader (the Führer) and promoted the idea of racial purity as central to national strength. This book became foundational for Nazi ideology and helped galvanize support once he was released from prison.

4. Shift to Legal Political Maneuvers

After his release in December 1924, Hitler shifted tactics from violent revolution to legal political engagement. He focused on building a mass movement through propaganda and electoral politics. The onset of the Great Depression in 1929 played a crucial role in this strategy; economic despair made extremist parties like the Nazis more appealing as they promised stability and national rejuvenation.

5. Electoral Successes

By July 1932, the Nazi Party became the largest party in the Reichstag with approximately 37% of the vote but did not achieve an outright majority. Despite this success, President Paul von Hindenburg was initially reluctant to appoint Hitler as Chancellor due to concerns over his radical agenda.

6. Appointment as Chancellor

On January 30, 1933, under pressure from conservative politicians who believed they could control him and use his popularity for their own ends, Hindenburg appointed Hitler as Chancellor of Germany. This appointment marked a critical turning point; although he was not yet an absolute dictator, it provided him with a platform from which he could dismantle democratic institutions.

7. Consolidation of Power

The Reichstag Fire in February 1933 allowed Hitler to persuade Hindenburg to issue an emergency decree that suspended civil liberties throughout Germany. This decree enabled him to arrest political opponents and suppress dissent effectively. Following this consolidation of power, the Enabling Act passed in March 1933 granted Hitler dictatorial powers by allowing him to enact laws without parliamentary consent.

8. Merging of Powers

With Hindenburg’s death on August 2, 1934, Hitler merged the offices of Chancellor and President into one position—Führer—solidifying his total control over Germany

The earth structure

Earth Structure

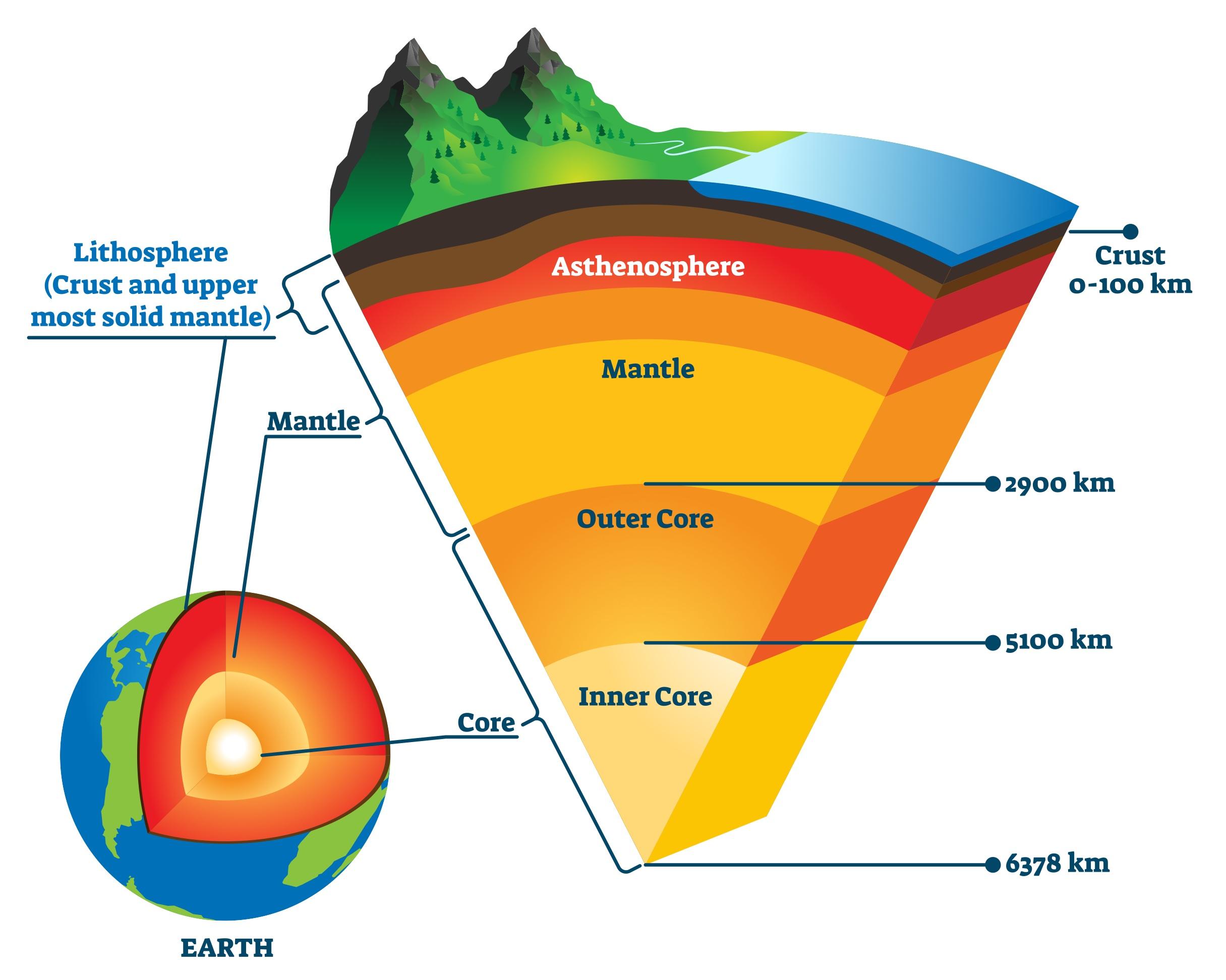

The structure of the Earth is a complex arrangement of layers, each with distinct physical and chemical properties. Understanding these layers is crucial for comprehending geological processes, including plate tectonics, earthquakes, and volcanic activity. The Earth can be divided into four main layers: the crust, the mantle, the outer core, and the inner core.

1. Crust

The crust is the outermost layer of the Earth and varies in thickness from about 5 kilometers (3.1 miles) beneath the oceans (oceanic crust) to about 70 kilometers (43.5 miles) beneath continental regions (continental crust). It is primarily composed of lighter elements such as silicon, aluminum, and oxygen. The crust is divided into two types:

- Oceanic Crust: This type is thinner and denser than continental crust, primarily made up of basaltic rocks.

- Continental Crust: This type is thicker and less dense, composed mainly of granitic rocks.

The boundary between the crust and the underlying mantle is known as the Mohorovičić discontinuity (or “Moho”), where there is a significant change in seismic wave velocity due to differences in rock density.

2. Mantle

Beneath the crust lies the mantle, which extends to a depth of about 2,890 kilometers (1,800 miles). The mantle constitutes approximately 84% of Earth’s total volume and is composed mainly of silicate minerals rich in iron and magnesium. It can be further divided into:

- Upper Mantle: This includes the asthenosphere, a semi-fluid layer that allows for tectonic plate movement.

- Lower Mantle: This region behaves more like a solid due to increased pressure but can still flow over geological timescales.

Convection currents within the mantle are driven by heat from radioactive decay and residual heat from Earth’s formation. These currents are responsible for moving tectonic plates on the surface.

3. Outer Core

The outer core lies beneath the mantle at depths ranging from about 2,890 kilometers (1,800 miles) to approximately 5,150 kilometers (3,200 miles). It is composed mainly of liquid iron and nickel and plays a critical role in generating Earth’s magnetic field through its convective motion combined with rotation—a process described by dynamo theory.

4. Inner Core

At Earth’s center lies the inner core, which extends from about 5,150 kilometers (3,200 miles) to approximately 6,371 kilometers (3,959 miles) below Earth’s surface. The inner core is solid due to immense pressure despite extremely high temperatures reaching up to 5,400°C (9,800°F). It consists primarily of iron with some nickel and possibly other light elements

-

Earth Structure The structure of the Earth is a complex arrangement of layers, each with distinct physical and chemical properties. Understa...

-

The Orange River, one of the longest rivers in South Africa, has a rich history that contributes to its name. The river’s origins can be tra...

-

Cold War The Cold War was a prolonged period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union, along with their resp...